This morning the TES published a confusing article on key findings from the Wellcome Trust Science Education Tracker. This is a survey of over 4000 young people Y10-Y13 asking about their views on their science education and careers. The TES don’t even seem to have managed a link but the tracker, including a breakdown of the questions and responses is at https://wellcome.ac.uk/what-we-do/our-work/young-peoples-views-science-education

Hopefully readers from the science education community might have quickly got past the ‘hands thrown up in horror’ headline and be asking whether the survey tells us anything useful about the quantity or quality of practical work in schools and colleges. Actually there are 144 questions and only 3 are about practical work. There is a mine of useful data here for questions around post-16 STEM participation, science capital, and availability and participation in triple GCSE, which has been a problematical issue, but that’s probably best seen through the lens of the ASPIRES2 work. Hopefully they’ll blog about the survey results at some point.

I’ve only had a quick look but these are my first impressions of the 3 questions (T66-T68) directly asking about practical work.

Firstly, some caution is always required when dealing with self-report measures, and also the way the responses are reported. For example (T66), young people might well have different views on what constitutes “Designing and carrying out an experiment / investigation” and “A practical project lasting more than one lesson” but I can’t see how any of last year’s Y10 or Y11 could not have completed an ISA across multiple lessons. The responses to these two questions were about 75% and 55% respectively with 10% responding “None of these”. What were the 10% doing? Did at least 35% squeeze an ISA into one lesson or do their ISAs in only one of the two KS4 years? How many didn’t think an ISA was an investigation (justifiably?). My take on this is that we need the responses to the same question for current Y10 to see the impact of the new GCSEs, otherwise we are discussing history, but I’m not convinced about the merits of practical projects and multiple-lesson investigations anyway.

Secondly, it’s important to interpret the findings critically. About 1/3 were happy with the amount of practical work and nearly 2/3 would have liked more. As pointed out in @alomshaha’s excellent video, this might be because practical is an easy option, not because it is the best way to improve learning. Even children have a keen awareness of this issue; in the Student Review of the Science Curriculum (Murray & Reiss 2003), about 70% had “Doing an experiment in class” in the top 3 most enjoyable activities (along with watching a video and going on a trip) but only about 40% thought it top 3 for “Most useful and effective activities”.

However, there is one thing in the data we ought to be thinking about. These are the figures for “When doing practical work, how often would you say that you just followed the instructions without understanding the purpose of the work?”

That suggests this statement is true for maybe 1/3 of practicals; this concurs with a lot of practice I see out in schools (from trainee teachers, mostly, but I have a suspicion it’s quite widespread). I think this is a problem.

It’s really good to see a School Science Review article by Millar & Abrahams (2009) here on the AQA website. This is a summary of a significant bit of work they, and some others, did looking at the effectiveness of practical work. Essentially the problem they identify is confusion over learning objectives. Just like all lesson planning, the objectives need to drive the activities, not the other way round. Whole-class practicals form such a big and obvious chunk of a lesson that it’s really easy to start planning from the activity. The trouble is that you then lose sight of the wood for the trees so that a successful practical outcome becomes the real objective – the one you focus on – although the lesson actually has an objective related to knowledge and application of science content. You then emphasise the procedure and just hope the children understand how it relates to the science content. And the children then just follow your instructions (hence the survey response) and, as Millar and Abrahams put it the emphasis becomes “producing the phenomenon”.

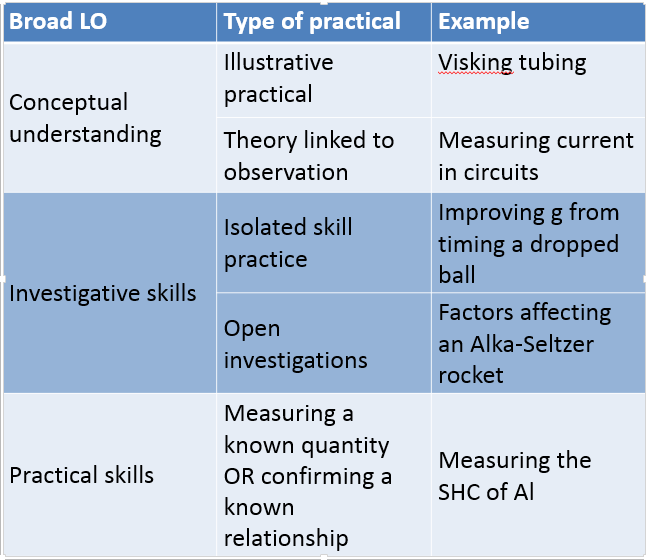

Millar and Abrahams go on to suggest there are three broad categories of learning objectives that are served by practical work and, based on a related article, I’ve broken these down further. I find this really helpful in getting a clearer focus on what purpose the practical serves in the lesson and therefore what the best way to approach it is.

If conceptual understanding is what you want, then the children need to spend time thinking about the practical in relation to the relevant content. There are maybe three options here:

- Whole class practical with lots of time afterwards to do work on how the practical is a demonstration of the content.

- Whole class practical with very high level of practical competence so children have capacity to think about the content.

- Demo or video (maybe simulation) so children don’t have to think about manipulating equipment and the teacher can direct their attention with questions and explanations.

The second of these could come from prior learning, but could also be a result of very careful briefing. This is, I think, what @oliviaparisdyer is describing in her blog post about practical work. It is certainly how I remember my excellent O-Grade Chemistry teacher doing it, several decades back into the last century.

If investigative skills are what you want then don’t try to teach conceptual understanding at the same time and remember that as science graduates we tend to massively underestimate the complexity of designing and conducting a full investigation. That’s why the ISAs were such an unpleasant exercise in trying to temporarily get children to remember enough to hit whatever ridiculous coursework target grade they had. I’ve had the good fortune to work with A-Level students on some terrific independent projects (for A-Level Physics and EPQ) but even post-16 they are barely ready for high-quality work. In my experience, either very high-levels of scaffolding, or acceptance of interesting but very rickety work, are needed for 11-16 classes, though that may not be true for all teachers.

Finally, if practical skills are what you want, then again you need to focus on them. Something like reaction of copper(II)oxide with sulfuric acid and then filtering and evaporating to get copper(II)sulfate involves a stack of excellent practical skills to do well. This would be a great practical for improving these skills; I think it’s a massive waste of time for learning the chemistry of metal oxide + acid reactions. By all means combine the two, so do the practical in that unit, and start or finish with the chemistry, but don’t expect the children to learn anything about the chemistry content whilst trying not to scald or gas themselves or – more hopefully – produce nice blue crystals.

This blog is already a bit long; next post I’ll try to use an example to explore these ideas about confused objectives a bit further, and then I’ll try and write another post on why children don’t automatically develop understanding from seeing a scientific principle ‘in the flesh’ and about Driver’s excellent Fallacy of Induction.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.